On the banks of the Indus River in Pakistan’s Mianwali District lies one of the most ambitious yet unrealized architectural dreams of the nation—the Kala Bagh Dam. Although construction never began, the dam’s detailed blueprints and design documents tell a story of vision, structural ingenuity, and a commitment to harnessing nature through architecture and engineering.

Historical Genesis – From Idea to Blueprint

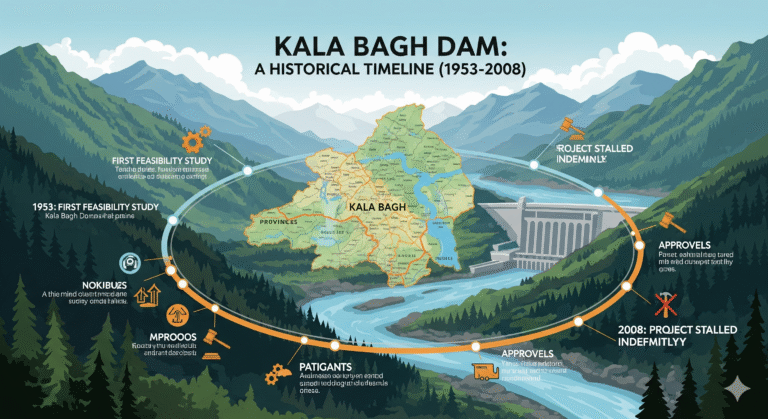

The idea of the Kala Bagh Dam first surfaced in 1953 as part of a broader irrigation plan. The fertile but underutilized lands near the Indus inspired engineers and architects to imagine a massive rock-fill dam that could transform agriculture and generate power.

By the 1960s, with the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), feasibility studies began. These early surveys laid the foundation for what would become one of the most technically detailed dam projects in South Asia.

In 1984, under the supervision of the World Bank and UNDP, the detailed architectural and engineering designs were finalized. The design called for a 260-foot-high rock-fill structure with a reservoir capacity of 7.9 million acre-feet (MAF) and hydroelectric potential ranging from 2,400 to 3,600 MW. By 1988, tender documents and full construction designs were ready, positioning the Kala Bagh Dam as a project that could start immediately.

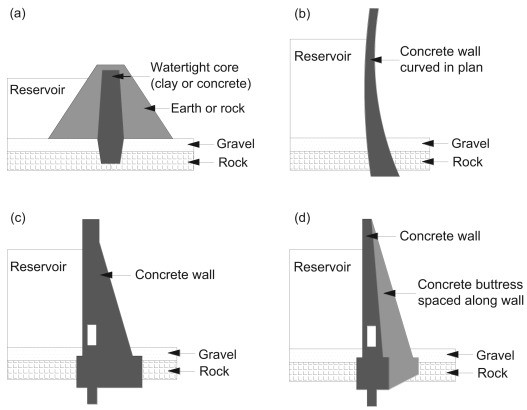

Architectural Vision and Technical Design

The proposed design of the Kala Bagh Dam was monumental in scale and precision. It was envisioned as a rock-fill dam, a type known for stability and durability. Its sheer mass would allow it to tame the Indus River, channeling water into controlled reservoirs.

Two massive spillways were designed to handle peak flood discharges of nearly 2 million cusecs, ensuring the structure could withstand the ferocity of the Indus during monsoon seasons. The powerhouse was designed with 12 conduits leading to turbines that could generate up to 3,600 MW of clean energy.

From an architectural standpoint, Kala Bagh wasn’t just about function—it was about balance. Its design integrated modern dam-building techniques with the natural geography of Mianwali, envisioning a landscape where technology and nature coexisted.

The Architects and Designers Behind the Vision

Large-scale public projects like Kala Bagh are rarely credited to a single name. Instead, institutions like UNDP, the World Bank, and Pakistan’s own Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) shaped its vision.

That said, notable Pakistani architect Abdur Rahman Hye, known for master planning government institutions across the country, influenced much of the regional development ethos at the time. While he wasn’t the dam’s direct architect, his approach to architecture—emphasizing adaptability, context, and durability—was echoed in projects like Kala Bagh

Architectural Milestones Through Time

- 1953 – Project inception as an irrigation scheme.

- 1960s – Feasibility studies funded by UNDP.

- 1984 – Detailed design prepared with World Bank oversight.

- 1988 – Technical documents finalized and ready for tendering.

- 2004 – The project was briefly revived in national planning.

- 2008 – Despite full technical readiness, construction never began.

How Architects Can Turn This Dream into Reality

The Kala Bagh Dam is more than just a technical challenge—it is a dream waiting for thoughtful architects to transform it into a legacy. With their ideas and commitment, architects can make sure the project serves people, not just power grids.

- Designing for Communities: Architects can ensure families living near the site are not displaced without hope. Instead, they can design modern resettlement villages with homes, schools, healthcare, and community centers—making life better than before.

- Balancing Nature and Structure: With ecological sensitivity, architects can integrate wetlands, wildlife passages, and green belts into the dam’s landscape, ensuring that it coexists with the environment instead of fighting it.

- Creating a Landmark of Pride: By embedding cultural motifs and local heritage in design—whether in service towns, visitor centers, or even the aesthetics of the structure—architects can turn the dam into a symbol of national pride.

- Listening to People: Architects can hold workshops and dialogues with local farmers, fishermen, and villagers, ensuring their voices shape the outcome. This transforms the dam from a government project into a community-owned vision.

- Innovating for the Future: With renewable energy add-ons, eco-tourism opportunities, and water-smart systems, the dam could become more than a utility—it could be an innovation hub for sustainable living.

Through such architectural leadership, the Kala Bagh Dam could evolve from paper to reality, uplifting millions of lives. For communities, it would mean secure water, clean energy, and modern living. For Pakistan, it would mean finally giving shape to a 70-year-old dream in a way that is humane, sustainable, and inspiring.

implementation while minimizing disruption.

Frequently Asked Questions

Not due to architectural or technical challenges—it was fully feasible—but for reasons beyond architecture.

Its primary goals were irrigation water storage and clean hydroelectric energy generation.

Detailed designs were completed in 1984, and tender-ready documents were finalized by 1988.

A reservoir of 7.9 MAF with power generation of 2,400–3,600 MW.

The project was institution-led, primarily by WAPDA, UNDP, and the World Bank. Individual architects are less documented, though regional planners like Abdur Rahman Hye influenced Pakistan’s infrastructure ethos.

Roughly 6–7 years, using modern machinery and construction technologies.

By adding sustainable elements, reducing ecological disruption, and designing with communities at the center.

Conclusion

The Kala Bagh Dam is not just an unrealized structure—it is a vision of what Pakistan’s architecture can achieve when combined with human-centered design and sustainability. It shows how architects are not only builders but custodians of community well-being and environmental balance.

If one day this project is revived, it has the potential to become more than a dam. It could be an architectural legacy—a place where water, energy, and people live in harmony.